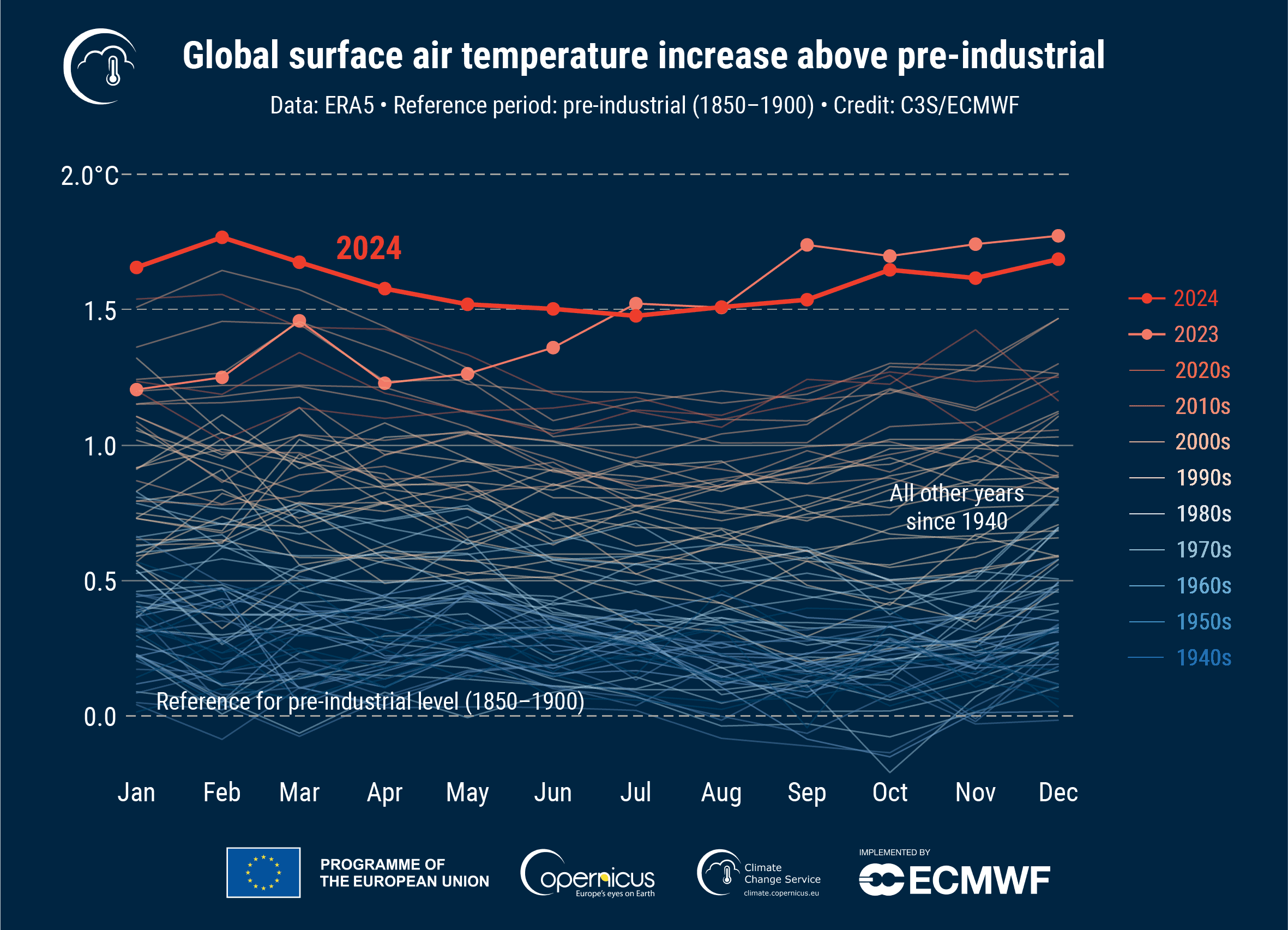

Since the Paris Agreement in 2015, the world has rapidly approached the 1.5°C global warming threshold. According to the European Copernicus Climate Change Service, 2024 is the first year to exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial level. This makes the goal of limiting warming to +1.5°C increasingly unrealistic – more of an illusion than an achievable target.

State of the oceans

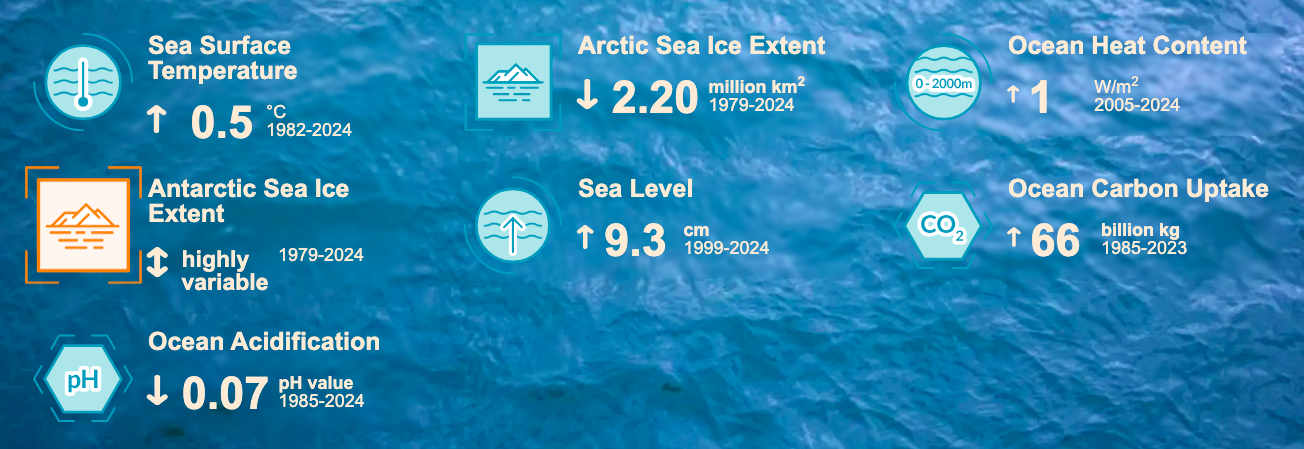

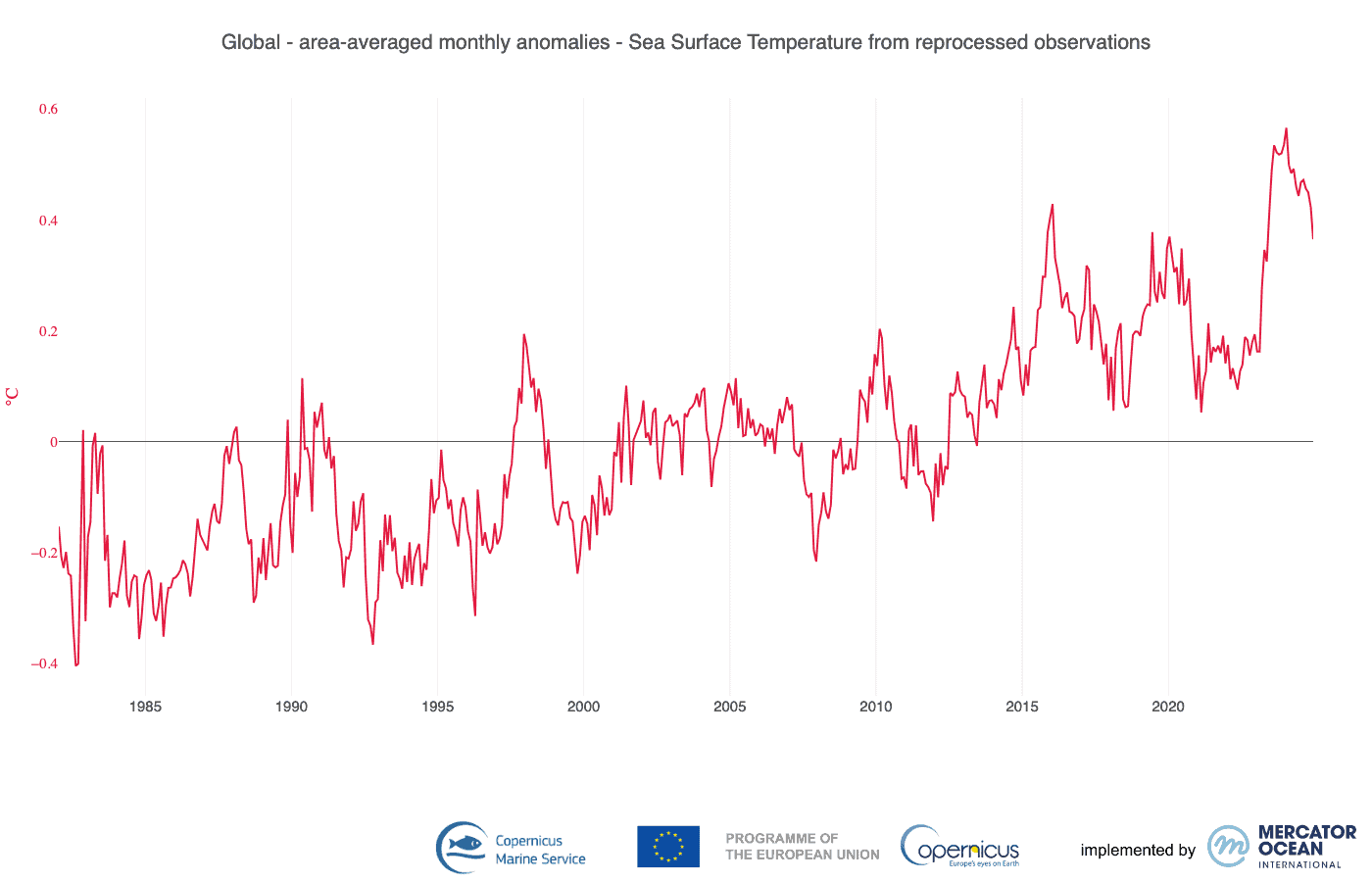

The oceans cover 75% of our planet and are vitals for ecosystems: regulating atmospheric temperature, producing oxygen, and absorbing about a quarter of atmospheric carbon dioxide. However, they and us face major threats:

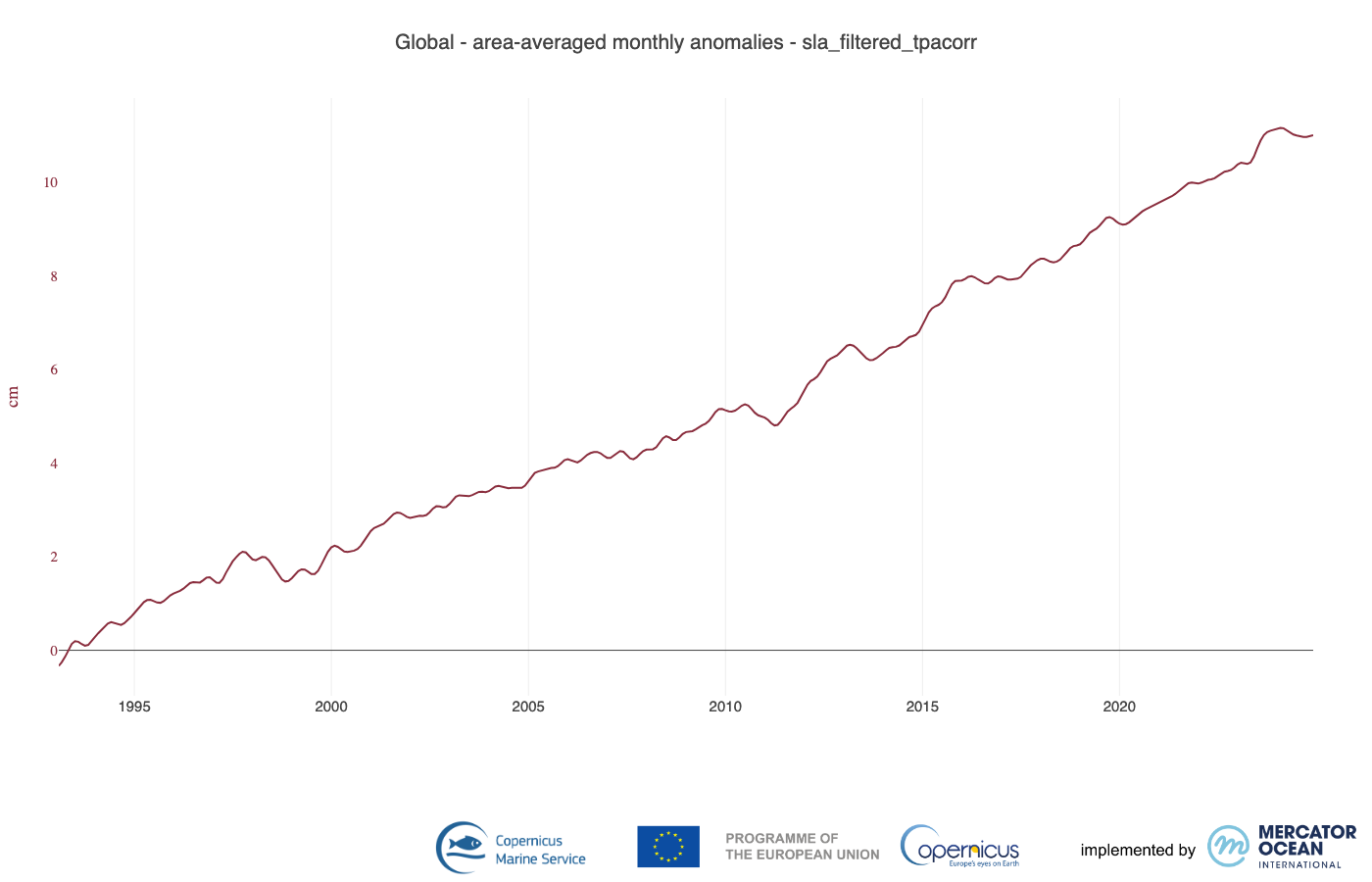

- Sea level rise from thermal expansion and melting glaciers due to global warming;

- Ocean acidification as CO₂ dissolves, lowering pH and forming carbonic acid;

- Heat release – oceans now return excess heat to the atmosphere, raising surface temperatures and endangering marine life;

- Marine pollution, which is devastating marine ecosystems.

The industrial agriculture paradox

Industrial agriculture feeds only for 30% of the world’s population, – mostly in the “global north” –, yet consumes 70% of global resources, including land and drinking water. Its impacts include:

- Environmental devastation. Even more significant damage in tropical forests, threatening humanity.

- Greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 30% of global emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, etc).

This imbalance highlights its inefficiency and heavy environmental cost. In contrast, sustainable agriculture rebuilds ecosystems. While industrial methods have turned the Amazon from a carbon sink into a CO₂ emitter, sustainable agriculture – using local knowledge in agroforestry, water conservation, and soil management – is restoring ecosystems, as seen in the Sahel’s recovery from drought. The contrast is undeniable: industrial agriculture destroys, sustainable agriculture restores.

From Baku to Belém

COP29 (Baku, Azerbaijan, 11–22 November 2024) – Major outcomes

- Carbon Markets Agreement: Parties approved UN rules for carbon trading between nations.

- Tripling Climate Finance: Developed countries agreed to increasing annual climate finance to developing nations from USD $100 billion to $300 billion by 2035. This funding includes a mix of grants, public loans, and contributions through multilateral development banks (World Bank, European Investment Bank, Asian Development Bank). Public loans and donations being counted in the same way. Developing countries had pushed for $1.3 trillion in public funds only, but this was rejected.

COP30 (Belém, Brazil, 10–21 November 2025) – Key Agenda Items

- Stronger National Climate Plans (NDCs): Countries must submit more ambitious plans to keep global warming below 1.5°C.

- Indigenous Participation: The inclusion of American indigenous peoples is a central issue.

The COP30 concluded without establishing a concrete roadmap.

Finance and accessibility Controversies:

- The $100 billion annual target was met two years late (2022 instead of 2020), according to the OECD.

- Oxfam estimates actual climate finance mobilization is about $30 billion – three times less than reported.

- Around 70% of climate finance is provided as loans, not grants.

- Countries self-report their contributions and figures, raising transparency concerns.

- High participation costs to COP (e.g., hotel prices) are excluding smaller and poorer countries, with some leaders (e.g., Austria’s president) canceling attendance to COP30 due to expenses.

The wave is coming

The science is unequivocal: to avoid the most devastating consequences of climate change and preserve a livable planet, we must limit global warming as much as possible – and we must do it urgently (IPCC report). At this stage, the wave is coming, and it will hit hard.

As history shows, developed countries are the main contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, and they continue to bear the greatest responsibility. Meanwhile, poorer nations – those least responsible – are already suffering the harshest impacts.

For adaptation efforts to succeed, they must be equitable and aimed at reducing social inequalities. But the COP process is still far from achieving this, and it may never fully do so, due to:

- the continued exclusion and marginalization of the most vulnerable populations (who make up the majority of the world),

- the overrepresentation – and dominance – of a small, powerful minority defined by gender, race, language, religion, political influence, and wealth.